It’s late August. You’re on a dock, a patio, or maybe globetrotting, all in the name of soaking up the last few weeks of summer. But then your phone buzzes to notify you of an email from the University of Ottawa. Your tuition is due next week, and—lucky you—it’s increased again. But does the scenario have to play out this way?

On the contrary, free tuition is a concept that has been implemented in countries like Finland, Germany, and Norway, but has yet to make a full appearance in Canada. The Ontario government has recently made strides in the same direction, with changes in its 2016 budget to improve access to education for those whose parents collectively make under $50,000 in annual income.

But is it enough to only subsidize tuition for those coming from a low-income background? The Fulcrum’s editorial board thinks we need to go further. With the Canadian Federation of Students’ nation-wide Day of Action event to fight for free tuition having already taken place, we believe it’s an ideal time to look at why Ontario should make free tuition standard practice—not just for low-income families, but for all.

For one thing, Ontario’s current provision in the name of free tuition is inherently inadequate, since the wealth of parents cannot be assumed to translate directly to student wealth. Many students are required to come up with the money for their own education due to anything from family values to poor family relations.

The state of the Ontario government’s assistance is only made worse by the tuition increases seen in universities. Tuition rates at the University of Ottawa have increased every year for the past decade. Combined with major decreases in government funding over the years, this situation makes it extremely difficult for students on a budget to further their education.

Not convinced that students deserve more government funding? Well, then just try getting through the next few decades without us.

With baby boomers retiring en masse, there’s more demand now than ever to fill the spaces that skilled workers are leaving behind as they head towards retirement. And, with the declining birth rate in Canada in recent years, it’s likely that our age group will be relied on for a greater span of time. With that in mind, educating as many students as possible is key to sustaining and strengthening Canada’s economy.

Even with free tuition there remains a slew of barriers to obtaining a university degree. As the Canadian dollar depreciates relative to the U.S. dollar, it becomes even more costly for students to buy the books they need. Not to mention costs for rent, groceries, laundry, the opportunity cost of not working full time… you know the rest. These costs add up, and if the government provides free tuition, this would tip the scales for more people in favour of attending.

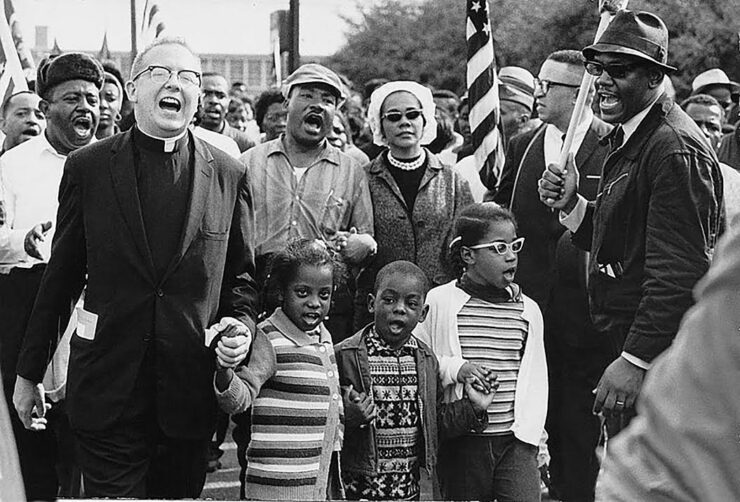

Providing free tuition is also a mechanism for alleviating the wage and educational attainment gaps seen in disenfranchised groups of society. According to Statistics Canada’s most recent report comparing median incomes in 2010, Indigenous people as a whole earned a median income of $27,866, while non-Indigenous people earned a median income of $38,657.

These income levels are reflective of the educational attainment levels reported by Statistics Canada in 2011, which show that nearly 30 per cent of Indigenous people in Canada held no certificate, diploma, or degree. This highly contrasts with the non-Indigenous population, where only 12.1 per cent held no certificate, diploma, or degree.

A conclusion made in this same 2011 Statistics Canada report is that employment rates and median total income increase with education. It seems that a major key to improving the socioeconomic status of Aboriginal people in Canada is to increase the access to education—and what better incentive is there to finish high school and attend university than a $0 bill?

Free tuition could also help the Canadian government save on its social assistance program expenses in the long-run. It was reported by Historica Canada in 2012-13 that Aboriginal people are more likely than non-Aboriginal Canadians to rely on social income assistance, with only 5 per cent of Canadians receiving assistance that year. In contrast, the same report shows 33.6 per cent of First Nations people received this aid, and in some Aboriginal communities that number can rise to highs of 80 per cent.

Despite this increased use of social assistance, 60 per cent of First Nations children are currently living in poverty.

With the introduction of free tuition in Canada, we would likely see positive changes in all of the aforementioned variables, regardless of the demographic of Canadians studied. Educational attainment and consequently Canada’s median income would likely see an increase. On the other hand, poverty and use of social assistance or unemployment programs would likely be drastically reduced.

Free tuition would strengthen the abilities of our youth and ensure equal opportunity for people of all backgrounds, creating a better Canada for generations to come. So, what is Canada waiting for?